Andrew Nicholls: The Year of the f**king Monkey

Andrew Nicholls: The Year of the f**king Monkey

Words by Thea Costantino

I write these words as the news of Donald Trump’s presidential election sinks in, the latest dispiriting moment of 2016; a year that Andrew Nicholls repeatedly tells me is cursed. He blames the cosmic influence of the Year of the Monkey, which happens to be the astrological sign I was born under. I don’t take his refrain of “f**king monkeys” personally; it’s true, we are living through grim times. The growing strength of a revanchist right wing movement that yearns to restore a pre-civil rights social order presents a tangible challenge to those who hope for a society based on equality and justice. This might seem like a strange opening for an artist profile on Andrew, but in fact it is a perfect entry point into the cultural themes that he grapples with in his practice as an artist-curator.

If I labour this point, it is because the decorative aesthetics of Andrew’s artwork sometimes lull his audience into a reverie that is both deceptive and biting. He employs materials and techniques traditionally marginal to the fine art canon, belonging to the ‘applied’ arts of illustration and craft, and his work is suffused with an ornamental aesthetic at odds with the self-professed modernity of contemporary Australia, or Anglophone culture in general.

The deployment of markers of luxury and desire in his work is political, in the sense that he follows the historical interplay of aesthetics and power.

Rather than offer a nostalgic image of the past, Andrew’s borrowing from historical sources draws out continuities and ruptures with history, such as Europe’s predatory relationship to its others, and shifting codes of male homoeroticism since the eighteenth century. Through exploring histories of the politics of taste, he is led to consider themes that continue to drive ideological rifts in contemporary life: imperialism, memory, gender and sexuality.

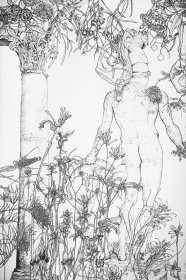

Andrew is probably best known for intricate pen drawings in which the restrained beauty of neoclassical modes is subverted by a hallucinatory frenzy of ornament. In Via Australiano Antica #1, for example, native Australian flowers frame the posterior view of a classical warrior in marble, replete with the cracks of deep age. The incongruity of this juxtaposition elegantly points to Australia’s fraught relationship to what was known as the ‘European inheritance’: the ostensible cultural lineage connecting ancient Greece and Rome with their more recent legatee, the British Empire and its colonial outposts. Around the time of Federation, the project of an Australian national identity based on classical and British imperial models was troubled by anxieties about the morality of the colony, an obsession with the maintenance of white racial supremacy, and a preoccupation with the decline of empires. Andrew’s intervention seems to suggest the receding of an idealised imperial past and its erosion by the forces of nature, an evocation of the Australian Gothic in which the white settler is haunted by the fear of a hostile and ill-gotten landscape.

Andrew is probably best known for intricate pen drawings in which the restrained beauty of neoclassical modes is subverted by a hallucinatory frenzy of ornament. In Via Australiano Antica #1, for example, native Australian flowers frame the posterior view of a classical warrior in marble, replete with the cracks of deep age. The incongruity of this juxtaposition elegantly points to Australia’s fraught relationship to what was known as the ‘European inheritance’: the ostensible cultural lineage connecting ancient Greece and Rome with their more recent legatee, the British Empire and its colonial outposts. Around the time of Federation, the project of an Australian national identity based on classical and British imperial models was troubled by anxieties about the morality of the colony, an obsession with the maintenance of white racial supremacy, and a preoccupation with the decline of empires. Andrew’s intervention seems to suggest the receding of an idealised imperial past and its erosion by the forces of nature, an evocation of the Australian Gothic in which the white settler is haunted by the fear of a hostile and ill-gotten landscape.

He applies a related strategy in his ceramic work, investing such genteel household objects as a dinner platter with imagery that spews forth anxieties and feverish desires properly supressed in bourgeois Australian society. His recycled Wembley Ware dinner service Bitter Heritage, for example, references the bleak narrative of Randolph Stowe’s novel Tourmaline, in which a messianic outsider is feted and then abandoned by a post apocalyptic mining town in Western Australia. In the composite image formed by the plates, crows feast upon the prostrate figure of the Water Diviner, lost in the desert, drawing our eyes towards the centre of the installation to meet the subject’s melancholy gaze and red-framed genitalia.

Across the broad range of his work, Andrew draws out and revels in posing threats to the colonialist and heteronormative values of contemporary culture.

Across the broad range of his work, Andrew draws out and revels in posing threats to the colonialist and heteronormative values of contemporary culture.

With such interests, it’s not surprising that he has been drawn to the life and legacy of Sigmund Freud, whose theories can offer a great deal when considering histories of power and desire. In 2013 he led a group residency with seven Western Australian artists, myself included, at Freud’s final house, now a museum, culminating in the 2015 exhibition An Internal Difficulty: Australian Artists at the Freud Museum London. Andrew’s curatorial practice is driven by a site-based methodology that requires artists to undertake research in specific places and to develop artworks in response to the experience.

It’s a particularly rewarding process as an artist, as it involves working as part of a collective and shaping the exhibition through a shared set of discoveries. Through his curation of the Freud Museum project, we participating artists were able to offer a range of responses to the site, which addressed overlapping concerns about gender, the body, desire and cultural memory.

An even more ambitious curatorial project currently in development is A Gentle Misinterpretation: Australian Artists and Chinoiserie, which has involved 13 artists and two site visits: the first at George IV’s extravagant Chinoiserie palace in Brighton, England, and the other at The Pottery Workshop in Jingdezhen, China. Andrew’s strategy for considering the West’s historical hunger for, and appropriation of, Asian aesthetics brings artists to specific sites of consumption and production, while allowing for counter narratives and points of contestation to emerge.

He explains, “Chinoiserie remains something of a guilty pleasure, via its undeniable aesthetic charm, but intensely problematic and kitsch appropriation of Asian culture. It reflects the worst excesses of colonial imperialism, yet reflects a level of fascination for the Asian ‘other’ that could be seen as (albeit naively) cosmopolitan in spirit. This exhibition invites a number Western Australian artists to develop new works investigating this aesthetic legacy.”

He explains, “Chinoiserie remains something of a guilty pleasure, via its undeniable aesthetic charm, but intensely problematic and kitsch appropriation of Asian culture. It reflects the worst excesses of colonial imperialism, yet reflects a level of fascination for the Asian ‘other’ that could be seen as (albeit naively) cosmopolitan in spirit. This exhibition invites a number Western Australian artists to develop new works investigating this aesthetic legacy.”

To try to encapsulate the multi-threaded nature of Andrew’s practice and his broad interests is not easy. I might hazard a sweeping generalisation and say that as a whole, his practice offers a critique of the project of European modernity and the horrific consequences born of attempts to craft this concept into reality. Andrew’s work lends itself to Freudian terms of interpretation; like an erotic nightmare, his work suggests the unbidden incursion of repressed material, tracing pathological tendencies in western culture through its appetites and symptoms. In this sense, he offers an important counter narrative and, perhaps, an antidote to the totalitarianism of our times.

Thea Costantino is an artist and writer who holds a PhD from Curtin University, where she works in the Faculty of Humanities. Thea is also a member of the Board of Directors of Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts. She has received a 2015 Visual Arts and Craft Mid-Career Fellowship from the Western Australian Department of Culture and the Arts, the 2013 Hutchins Art Prize, a 2011 Qantas Foundation Encouragement of Australian Contemporary Art Award and the 2012 Artsource/Gunnery Artist Exchange.

Images top to bottom:

-

Andrew Nicholls in his studio at The Pottery Workshop, Jingdezhen, China, in May, 2016. Image: Nathan Beard

-

Andrew Nicholls, Via Australiano Antica #1, 2015. Archival ink pen on watercolour paper, 106 x 77 cm. Image: Bradley Hammond, c/o the Kedumba Collection of Australian Drawings.

-

Andrew Nicholls, Bitter Heritage (for Randolph Stow), 2013. Decal print on recycled Wembley Ware dinnerware, approximately 1.5 x 2.5 m. Image: the artist

-

Andrew Nicholls, Production still from Gulchenrouz, 2015. Image: Casey Ayeres with thanks to the Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton